What happens when a state’s ambitious plan to combat deadly air pollution and harness clean energy collides with the deep-rooted fears of its rural backbone? In Punjab, a pioneering push to transform paddy straw into biogas is sparking both hope and hostility. As smoke from stubble burning continues to choke northern India each harvest season, the government’s vision of compressed biogas (CBG) plants offers a lifeline. Yet, in the villages meant to anchor this green revolution, resistance is mounting. This clash between policy and people raises a pressing question: can environmental progress coexist with rural realities?

A Green Dream Meets a Rural Divide

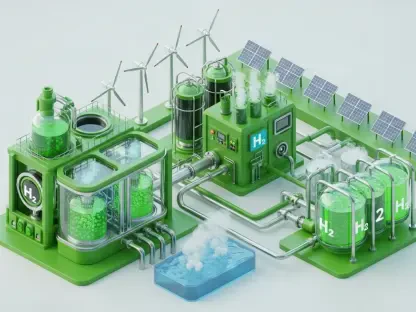

The significance of Punjab’s biogas initiative cannot be overstated. Stubble burning, a decades-old practice to clear fields after harvest, releases toxic pollutants that contribute to severe air quality crises across the region, impacting millions. Converting this agricultural waste into renewable energy through CBG plants promises not only to curb pollution but also to create a sustainable fuel source. With over 60 projects in development and a target to process massive quantities of straw annually, the stakes are high. However, the growing pushback from rural communities, who see these plants as threats to their land and livelihoods, underscores a critical tension that could derail this environmental breakthrough.

This story matters because it reflects a broader global challenge: balancing ecological imperatives with social equity. Punjab’s journey toward clean energy is a microcosm of how technological solutions often stumble when they fail to account for human concerns. The outcome of this struggle could set a precedent for similar initiatives in agricultural heartlands worldwide, making it essential to understand why villagers are resisting and how trust can be rebuilt.

The Scale of Punjab’s Biogas Ambition

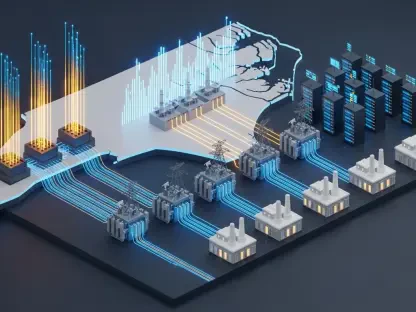

Punjab’s battle against stubble burning is backed by a robust framework led by the Punjab Pollution Control Board and the Punjab Energy Development Agency. The plan targets the management of nearly 1.5 million tons of paddy straw annually through ex-situ methods, with a significant portion—around 1.17 million tons—feeding into 11 biomass power projects that generate 101.5 MW of electricity. Beyond this, the state has rolled out an expansive network of CBG plants, with 60 projects boasting a combined capacity of 852.68 tons per day. Six of these plants are already operational in districts like Khanna and Sangrur, processing 250,000 tons of straw and contributing 107.48 tons per day to the energy grid.

The momentum continues to build, with four additional plants slated for commissioning by the 2025–26 fiscal year and 50 more in the pipeline over the next 18 to 24 months, involving major corporate players like HPCL and GAIL. Collaborative efforts with public sector units aim to establish 22 further CBG facilities, targeting the processing of 940,000 tons of straw each year. These numbers paint a picture of a state committed to transforming agricultural waste into a cornerstone of renewable energy, yet the real test lies not in infrastructure but in community acceptance.

Roots of Resistance in Rural Punjab

Despite the promise of cleaner air and economic benefits, rural Punjab is not embracing the biogas boom with open arms. Land, a precious and often scarce resource, sits at the heart of the opposition. In Kakrala village of Patiala’s Nabha block, a proposed CBG plant on 18 acres of common land was outright rejected by the gram sabha, as villagers insisted the space be reserved for farming by landless families. This prioritization of immediate agricultural needs over industrial projects highlights a fundamental clash of values.

Beyond land disputes, fears of environmental harm fuel the discontent. Many villagers recall past industrial ventures that left behind pollution and broken promises, fostering skepticism about the safety of biogas plants. In areas like Bagga Kalan in Ludhiana, concerns about emissions and waste disposal have sparked protests, with locals wary of health risks. Additionally, distrust runs deep when it comes to assurances of jobs and development—benefits often touted by officials rarely seem to trickle down to those most affected, further widening the gap between policy goals and rural realities.

Voices from the Fields Echo Discontent

The human dimension of this conflict comes alive through the words of those on the ground. “They talk about progress, but what about the smoke and stench these plants might bring to our homes?” questions a farmer from Ghungrali village in Ludhiana, capturing a widespread apprehension about living near industrial setups. Such sentiments are not isolated; across Punjab’s countryside, communities express frustration over being sidelined in decisions that directly impact their environment and daily lives.

Environmental expert Col. Jasjit Singh Gill offers a pragmatic perspective, suggesting that locating plants at least 2.5 miles from residential areas and enforcing rigorous waste management protocols could alleviate many concerns. Meanwhile, some plant operators are attempting to mend fences—KK Kaushal in Ghungrali, for instance, has distributed free fertilizers to local farmers as a gesture of goodwill. Yet, these efforts often pale against larger operational hiccups, as seen when protests in the same village halted a plant’s functioning for six months. Official data warns that without genuine public buy-in, even ambitious targets like utilizing 550,000 tons of straw this year remain in jeopardy.

Pathways to Harmony Between Policy and People

Addressing rural resistance demands more than lofty promises; it requires concrete, community-centric solutions. Transparency stands as a critical first step—organizing open forums with gram sabhas to discuss land allocation and pollution safeguards can help demystify CBG projects and dispel myths. Such dialogues must be paired with commitments to tangible benefits, like reserving a percentage of jobs for locals and allocating funds for village development, ensuring that communities see direct gains from hosting these plants.

Further, adopting expert advice on plant placement and environmental oversight is essential. Allowing panchayats to conduct regular inspections and mandating strict emission controls can build confidence in the safety of these facilities. Pilot initiatives, similar to the fertilizer distribution in Ghungrali, could also serve as small but powerful proofs of intent, demonstrating how biogas plants can contribute positively to rural life. If scaled thoughtfully, these measures could transform opposition into partnership, aligning Punjab’s green energy goals with the aspirations of its villages.

Reflecting on a Contested Green Legacy

Looking back, Punjab’s biogas journey revealed a profound struggle to reconcile environmental innovation with rural priorities. The state’s determination to tackle stubble burning through CBG plants marked a bold step toward sustainability, supported by impressive infrastructure and corporate backing. Yet, the resistance from villages like Kakrala and Ghungrali exposed a critical oversight: progress cannot be imposed without addressing local fears and needs.

Moving forward, the path to success hinges on fostering genuine collaboration. Engaging communities through consistent dialogue, ensuring equitable benefits, and implementing stringent safety measures emerged as non-negotiable steps to bridge the divide. If Punjab could refine this balance, it had the potential to not only curb pollution but also inspire other regions to pursue green transitions with empathy and inclusion at their core. The challenge ahead lay in turning policy ambition into a shared victory, proving that clean energy could indeed power both progress and trust.