Today we are joined by Christopher Hailstone, a leading expert in energy management and grid security. We’ll be delving into the recent severe storm that has battered New Zealand’s North Island, causing widespread disruption. Our discussion will cover the cascading failure of critical infrastructure, the immense pressure on emergency and utility crews, the often-overlooked public health risks that emerge after the floodwaters recede, and what this event signals for the country’s preparedness as the storm system moves south.

With major transport hubs like Wellington airport pausing operations and roads closing across the North Island, what are the cascading effects on supply chains and local communities? Please describe the typical protocol for coordinating such a widespread shutdown and the eventual resumption of services.

The shutdown you’re seeing is a necessary, albeit painful, defensive measure. When a storm of this magnitude hits, the first priority is always human safety. Authorities at airports like Wellington, Napier, and Palmerston North don’t make the decision to pause operations lightly; they’re looking at wind shear, visibility, and ground conditions. This immediately isolates communities and halts the flow of essential goods, mail, and personnel. The cascading effect is immense—supermarket shelves can empty, medical supplies can be delayed, and economic activity grinds to a halt. The protocol for resumption is a meticulous, step-by-step process. It begins with damage assessments of runways and roads, followed by safety checks of navigation systems and power grids, and only then can services be gradually and cautiously restored as conditions permit.

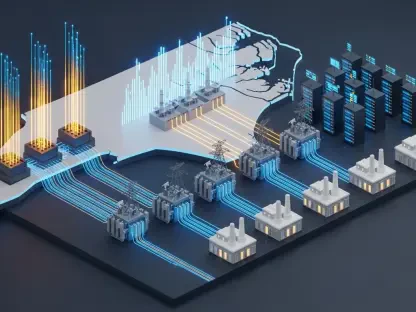

Emergency services received over 850 calls overnight, while 30,000 properties lost power. How do crews prioritize these simultaneous emergencies, from power restoration to urgent rescues? Could you share some specific challenges they face when infrastructure like roads and power grids are compromised?

It’s a process of brutal triage, frankly. With over 850 emergency calls, you have to immediately categorize them based on life-threatening situations. A person trapped in a submerged vehicle or a home threatened by a landslide takes absolute precedence over a flooded basement or a downed tree. Simultaneously, utility crews dealing with the 30,000 power outages are doing their own triage. They prioritize restoring power to critical infrastructure—hospitals, emergency shelters, and communication towers. The greatest challenge is the system-wide failure. A collapsed road, like the one we saw in the Waikato region, doesn’t just block a route; it might prevent firefighters from reaching a call or stop utility trucks from accessing a downed power line, creating a dangerous domino effect where one problem compounds another.

We’ve seen images of flooded homes and collapsed roads, and one resident described the storm as “absolutely terrifying.” Beyond the immediate damage, what are the long-term public health concerns, especially with incidents like raw sewage being washed onto the coast? Describe the recovery process for affected neighborhoods.

The immediate visual horror of flooded homes and fallen trees often masks the more insidious long-term threats. When floodwaters recede, they leave behind a toxic cocktail of contaminants. The incident in Wellington, where raw sewage was washed back onto the coast, is a particularly alarming example. This creates a significant risk of gastrointestinal illnesses and other waterborne diseases for anyone coming into contact with the water or contaminated ground. The recovery for a neighborhood is painstaking; it involves not just structural repairs, but also extensive sanitation, testing of water sources, and monitoring for mold growth in homes, which can cause chronic respiratory issues for years to come. It’s a silent health crisis that unfolds long after the storm has passed.

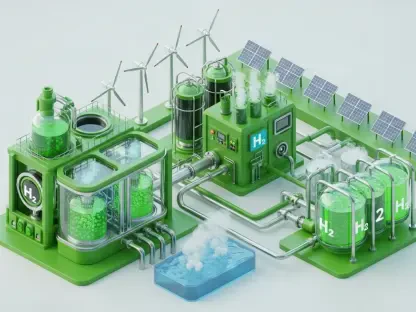

As this storm system moves toward the South Island, what specific lessons have been learned from the North Island’s experience to improve public warnings and preparedness? What immediate steps can authorities and residents on the South Island’s east coast take to mitigate potential damage?

The most critical lesson is that the ferocity of these systems can exceed forecasts, and infrastructure is more vulnerable than we often assume. The North Island’s experience underscores the need for proactive, not reactive, warnings. For the South Island, this means authorities must now issue starkly clear alerts about the specific risks of flash flooding, road collapses, and widespread power outages. Residents on the east coast should be taking immediate steps: securing outdoor property, clearing gutters and drains to help with water runoff, preparing an emergency kit with supplies for at least three days, and, most importantly, heeding all official advice to stay off the roads. Assuming you will be fine is the biggest mistake anyone can make right now.

What is your forecast for the frequency and intensity of these severe weather events in New Zealand over the next few years?

My forecast, based on the patterns we are observing globally, is not optimistic. These high-intensity rainfall and wind events are becoming the new norm, not an anomaly. The storm that just hit the North Island, coming so soon after the deadly landslide at Mount Maunganui, is a clear signal. We should anticipate that New Zealand will face more frequent and more powerful storms in the coming years. This requires a fundamental shift in how we approach infrastructure planning, civil defense, and public education. We must move from a mindset of recovery to one of proactive resilience, building our communities and power grids to withstand the inevitable weather that is to come.