The most significant breach of a nation’s critical infrastructure might not begin with a sophisticated, never-before-seen cyberweapon, but with a forgotten password on an unpatched firewall. A new and alarming front has opened in cyber warfare, where Russia-linked threat actors are systematically sidestepping complex exploits in favor of a simpler, more insidious strategy. This tactical evolution involves targeting the ubiquitous yet often overlooked edge devices—firewalls, routers, and VPN concentrators—that form the digital border between an organization and the open internet. By exploiting known vulnerabilities in this equipment, these adversaries gain a persistent foothold deep within their targets. This article dissects this emergent threat, detailing the attackers’ methods, the profound risks posed to critical infrastructure, and the essential defensive strategies organizations must adopt to secure this new frontline.

Introduction A New Frontline in Cyber Warfare

The emergent threat from sophisticated, state-sponsored actors linked to Russia represents a calculated pivot in cyber-espionage and warfare. These groups, including those associated with Russia’s military intelligence agency (GRU), have demonstrated a sustained focus on compromising organizations vital to national security and economic stability. Their operations target electric utilities, telecommunications providers, and managed service providers who form the backbone of the energy sector’s supply chain. This deliberate targeting signals a long-term strategic interest in gaining access to, and potentially disrupting, the foundational services that modern societies depend on. The sustained nature of this campaign, which has been active for several years, underscores the persistent and patient approach of these adversaries.

This campaign is defined by a significant tactical shift away from the high-cost, high-risk development of zero-day exploits. Instead, attackers are exploiting known, and often unpatched, vulnerabilities in common network edge devices. This approach is brutally efficient, leveraging security oversights and inconsistent patching cadences that are all too common in complex corporate and industrial environments. By targeting equipment from major vendors like Cisco, Palo Alto Networks, and Fortinet, these hackers exploit a vast attack surface, turning an organization’s own network perimeter into a gateway for intrusion. This method allows them to achieve their objectives—credential harvesting and lateral movement—with a fraction of the effort and a much lower chance of being detected.

The focus of this guide is to provide a clear and actionable framework for understanding and countering this evolving threat. It will first explore the strategic rationale behind the attackers’ choice to target edge devices, highlighting the operational advantages this method provides. Subsequently, it will delve into a series of best practices designed to fortify the network perimeter against such intrusions. By presenting detailed defensive measures, from hardening network endpoints to implementing a Zero-Trust architecture and enhancing monitoring capabilities, this article aims to equip security leaders and network administrators in critical sectors with the knowledge needed to build a resilient defense against a determined and resourceful adversary.

The Strategic Advantage Why Edge Devices Are Prime Targets

The decision by Russia-linked hackers to prioritize known vulnerabilities in edge devices over developing novel zero-day exploits is a masterclass in strategic efficiency. Developing a zero-day is a resource-intensive endeavor that requires deep technical expertise, significant financial investment, and a high tolerance for risk. Once deployed, a zero-day exploit is often quickly discovered, patched, and rendered useless, forcing the attacker to begin the costly development cycle anew. In contrast, targeting publicly disclosed but unpatched vulnerabilities in widely used networking equipment offers a far greater return on investment. The attackers leverage a pre-existing and widespread problem—patching inertia—to achieve their goals with minimal custom development.

This approach delivers a cascade of benefits for the adversary. First, it dramatically reduces the effort and cost associated with gaining initial access. Instead of crafting a unique digital key, they are simply walking through a door that has been left unlocked. Second, this method significantly lowers the probability of detection. Security tools are often calibrated to find novel or anomalous activity, whereas traffic originating from a known exploit can blend into the background noise of the internet, making it harder to distinguish malicious activity from benign scans. Most importantly, compromising an edge device provides the perfect staging ground for high-impact follow-on attacks, such as intercepting network traffic to harvest credentials. These stolen logins become the keys to the kingdom, enabling lateral movement into cloud platforms, corporate networks, and even sensitive operational technology (OT) environments.

The implications for national security and economic stability are profound. Critical infrastructure is not a monolithic entity but a complex, interconnected ecosystem of operators and third-party service providers. A breach at a single managed service provider specializing in the energy sector can create a ripple effect, granting attackers access to dozens of downstream utility companies. This makes protecting the supply chain as critical as securing the primary operators themselves. Consequently, the need for proactive security measures has never been more urgent. A reactive posture is no longer sufficient; organizations must assume they are being targeted and take decisive steps to harden their digital perimeters before they become the next vector for a widespread attack.

Fortifying the Perimeter Actionable Best Practices for Defense

To effectively counter this calculated threat, organizations must adopt a defense-in-depth strategy that begins at the network’s edge but extends throughout the entire enterprise. It is no longer enough to rely on a simple firewall to protect critical assets. The fight against these advanced persistent threats requires a multi-layered approach that combines proactive hardening, strict access controls, and vigilant monitoring. This defensive framework is designed to not only prevent initial compromise but also to detect and contain intruders who manage to find a way in.

Implementing these measures is a shared responsibility, requiring close collaboration between security teams, network administrators, and IT leadership. The following sections provide clear, step-by-step guidance on the three core pillars of a resilient perimeter defense. Each practice is designed to be actionable, offering practical instructions that can be implemented to immediately raise the cost and complexity for an attacker attempting to breach the network. By systematically applying these principles, organizations can transform their network edge from a vulnerable entry point into a formidable barrier.

Harden and Sanitize Network Edge Points

The first and most critical step in defending against this threat is to conduct a comprehensive audit and hardening of all internet-facing devices. This process begins with a meticulous inspection of every firewall, router, VPN appliance, and network management interface for any signs of compromise. Security teams should search for unauthorized configuration changes, suspicious files, or unusual network traffic patterns that could indicate an attacker is already present. This forensic review establishes a clean baseline from which to build a stronger defense, ensuring that existing backdoors are closed before new fortifications are erected.

With a sanitized environment, the focus shifts to two fundamental security practices: timely patching and attack surface reduction. Organizations must implement a rigorous patch management program to ensure that all known vulnerabilities are remediated as soon as updates become available. This closes the very security gaps that attackers are actively exploiting. Simultaneously, network administrators must reduce the unnecessary exposure of these devices to the internet. This involves disabling non-essential services, closing unused ports, and restricting administrative access to a limited set of internal, trusted IP addresses. Every service exposed to the internet is a potential entry point, and minimizing this exposure is a simple yet powerful way to reduce risk.

Case Study The GRUs Credential Harvesting Campaign

The operational playbook of Russia’s military intelligence agency, the GRU, provides a stark illustration of these risks. In a sustained campaign targeting critical infrastructure, hackers associated with the group systematically scanned for and exploited unpatched firewalls and network interfaces. Once they gained control of these edge devices, they reconfigured them to intercept and log unencrypted network traffic. This man-in-the-middle position allowed them to passively collect usernames and passwords as employees logged into various internal and cloud-based services. Armed with these legitimate credentials, the attackers could then move laterally from the compromised perimeter into the core network, often undetected for extended periods.

Implement Zero-Trust Access and Network Segmentation

Assuming a breach of the perimeter is inevitable, the next layer of defense focuses on containment. A Zero-Trust access model is essential, shifting the security paradigm from “trust but verify” to “never trust, always verify.” This principle should be enforced by implementing strong, phishing-resistant multi-factor authentication (MFA) for every service, application, and user account without exception. Requiring a second factor of authentication, such as a physical security key or a biometric scan, ensures that a stolen password alone is not enough for an attacker to gain access to sensitive systems. This simple control acts as a powerful barrier against credential-based attacks.

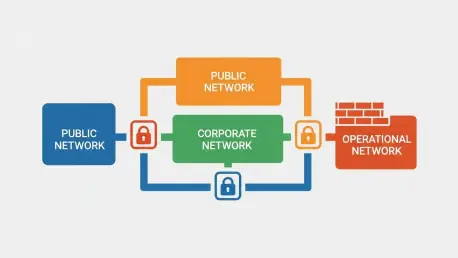

In parallel, network segmentation is a critical architectural control for limiting the blast radius of a successful breach. By dividing the network into smaller, isolated zones, organizations can prevent an attacker from moving freely from a compromised device into more sensitive areas. For example, the network segment containing internet-facing web servers should be completely isolated from the corporate network, which in turn should be firewalled off from the highly sensitive operational technology (OT) networks that manage industrial control systems. This compartmentalization ensures that a compromise in one area does not automatically lead to a catastrophic failure across the entire enterprise.

Real-World Impact Containing a Breach in the Energy Sector

The value of this strategy was demonstrated when a major utility company, having already implemented robust network segmentation, discovered a compromise on a network management device. The attackers had successfully exploited a known vulnerability to gain a foothold, but their ambitions were thwarted by the network’s architecture. The compromised device was located in a management subnet that had no direct network path to the critical OT systems controlling the power grid. The breach was effectively contained, allowing the security team to isolate and remediate the affected device without any impact on essential operations, turning a potential crisis into a manageable security incident.

Enhance Visibility Through Continuous Monitoring

A hardened and segmented network is a strong defense, but it is incomplete without comprehensive visibility. Effective security requires continuous monitoring and logging to detect threats that bypass preventive controls. Organizations must configure all edge devices, authentication servers, and critical systems to generate detailed logs of all activity. These logs should be centralized in a security information and event management (SIEM) system, where they can be correlated and analyzed for suspicious patterns. Best practices include actively reviewing logs for repeated failed login attempts, successful logins from unusual geographic locations, and attempts to access sensitive systems outside of normal business hours.

This monitoring should be enhanced with proactive threat hunting, which involves actively searching for threats rather than waiting for an automated alert. Security teams can leverage shared threat intelligence, such as Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) published by government agencies and security firms, to hunt for malicious activity within their own environments. IOCs can include lists of malicious IP addresses, file hashes, or domain names associated with a known attack campaign. By regularly scanning logs and network traffic for these indicators, organizations can often identify and neutralize an intrusion in its earliest stages, before significant damage occurs.

Example Proactive Threat Hunting with Shared Intelligence

Consider a telecommunications company that receives an intelligence report detailing the GRU’s campaign, including a list of command-and-control IP addresses used by the attackers. Their security team immediately initiated a proactive threat hunt, using the provided IOCs to scan their historical VPN and firewall logs. This search revealed that an IP address from the list had been attempting to authenticate to their VPN concentrator for several weeks. While the attempts had so far been unsuccessful, this discovery allowed the team to block the malicious IP, reset the credentials of the targeted account, and implement additional monitoring, thwarting an active intrusion attempt before it could escalate.

Conclusion A Call for Vigilance in Critical Sectors

The sustained focus of state-sponsored actors on the network edge served as a powerful reminder of the evolving threat landscape. This analysis demonstrated that these adversaries had adopted a highly efficient strategy, leveraging common security oversights in critical infrastructure to achieve significant operational outcomes. Their shift from developing complex zero-day exploits to exploiting known, unpatched vulnerabilities underscored a critical lesson for defenders. It became clear that the most effective defense was not found in expensive, next-generation technologies but in the disciplined and consistent application of fundamental security hygiene.

The case studies examined throughout this guide highlighted the tangible impact of both vulnerabilities and defensive measures. The success of the GRU’s credential harvesting campaign was a direct result of unpatched systems and weak access controls, while the energy sector breach was successfully contained thanks to proactive network segmentation. These examples proved that strategic investment in foundational security practices yielded a disproportionately high return in resilience. They reinforced the conclusion that while the attackers’ tactics evolved, the principles of a strong defense remained constant.

Ultimately, the guidance for operators in energy, telecommunications, and other vital sectors pointed toward a necessary cultural shift. Perimeter security could no longer be viewed as a purely technical IT function but had to be elevated to a core business priority, integral to operational resilience and national security. The key takeaway was that vigilance at the network’s edge, combined with a commitment to security fundamentals like patching, segmentation, and monitoring, was the most reliable strategy for protecting the essential services upon which society depends.