The global transition toward electric vehicles is widely celebrated as a monumental step in combating climate change, yet this green revolution casts a long and ominous financial shadow over the world’s most vulnerable economies. As electric cars replace their gasoline-powered predecessors, a primary and often overlooked source of government income—the fuel tax—is rapidly diminishing. A recent analysis revealed that this tax stream, which amounted to approximately $920 billion globally in 2023, is not just a line item in a budget but a fiscal bedrock for many nations. The erosion of this revenue base poses a universal challenge, but the severity of its impact is far from uniform. For developing countries, where this income is a disproportionately large share of the national budget, the shift from the gas pump to the charging port represents not just an environmental adjustment but a looming economic crisis that threatens to undermine public services and destabilize fragile economies.

The Widening Fiscal Divide

A Disproportionate Burden

The concept of “fuel tax transition exposure” provides a stark measure of this disparity, revealing a deep vulnerability that is concentrated in the developing world. Across 168 nations analyzed, a clear pattern emerges based on income level. While most countries rely on fuel taxes for a significant 4% to 8% of their total government revenue, this figure frequently exceeds 9% in lower-income countries. This statistical difference translates into a staggering reality: these nations are approximately three times more exposed to the financial shock of dwindling fuel tax income compared to their more affluent counterparts. This heavy reliance is not accidental; fuel taxes have long been a favored fiscal tool in developing economies because they are relatively straightforward to administer and collect at a limited number of points (refineries or import terminals), providing a stable and predictable source of funds for essential services like infrastructure, healthcare, and education. As this reliable revenue stream evaporates, the fiscal foundation of these states is put at risk.

The Compounding Crisis of Double Exposure

For many developing nations, the loss of fuel tax revenue is not an isolated problem but one component of a “double exposure” that creates a perfect storm of economic hardship. Countries such as Yemen, Benin, Mozambique, and Kenya exemplify this precarious situation, where a high dependency on fuel taxes converges with two other critical vulnerabilities: substantial national debt and weak institutional capacity. This toxic combination severely constrains their ability to adapt. While wealthier nations can leverage robust government machinery and fiscal flexibility to design and implement alternative tax schemes, these countries lack the administrative infrastructure and financial leeway to pivot effectively. They are caught in a debilitating cycle where falling revenues make it harder to service existing debt, further limiting their ability to invest in the very systems needed to create new, sustainable income streams. This double exposure threatens to trap them in a state of perpetual fiscal crisis, hampering their development and deepening global inequality.

Navigating a Perilous Transition

The Challenge of Alternative Revenue Streams

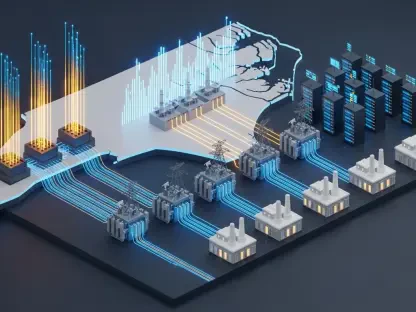

As governments search for ways to fill the fiscal void left by the EV transition, a range of potential solutions has emerged, including carbon taxes, road tolls, and new levies on electricity or EV imports. However, the viability of these alternatives varies dramatically between developed and developing economies. Higher-income countries are already beginning to experiment with and implement these measures, leveraging advanced technological infrastructure and established administrative systems. In contrast, these options present formidable challenges for lower-income markets. Establishing a comprehensive road toll system, for example, requires significant upfront investment in technology and infrastructure that many cannot afford. Similarly, taxing electricity consumption could disproportionately burden the poorest citizens and prove difficult to administer in regions with inconsistent power grids or high rates of informal energy access. An import tax on EVs, while seemingly straightforward, could slow the adoption of cleaner technology, undermining the very environmental goals the transition aims to achieve.

A Dual Threat for Resource-Rich Nations

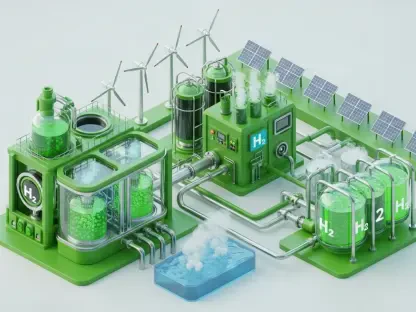

The economic predicament becomes even more complex for major fossil fuel producers like Nigeria and Angola, which face a dual threat from the global shift to electric vehicles. This transition attacks their economic stability from two distinct angles, creating a far more severe shock than that experienced by other developing nations. Firstly, they must contend with the same erosion of their domestic fuel tax base as consumers switch to EVs. Secondly, and more fundamentally, the very foundation of their national economies—the revenue generated from oil and gas exports—is directly undermined by falling global demand for fossil fuels. This dual impact jeopardizes not only their government budgets but also the returns on massive state investments in the oil and gas sector. For these nations, the EV shift is not merely a fiscal challenge but an existential threat to their long-standing economic models, demanding a profound and rapid diversification that is incredibly difficult to achieve under mounting financial pressure.

A Path Toward Equitable Decarbonization

The global push for decarbonization ultimately revealed that an environmentally sustainable future could not be built upon a foundation of economic inequality. It became clear that allowing the most vulnerable nations to navigate the fiscal shocks of the EV transition alone was an untenable path that risked deepening poverty and instability. In response, a concerted effort led by international institutions like the World Bank and the UN Development Programme became essential. The focus shifted from simple financial aid to providing crucial technical expertise and capacity-building support. This collaborative approach helped developing countries design and implement new, fair, and efficient revenue systems tailored to their unique circumstances, ensuring that the transition to electric mobility did not come at the cost of public services and economic progress. This proactive partnership ensured that the green revolution became a truly global success, one where climate action and economic justice were pursued as inseparable goals.