We’re thrilled to sit down with Christopher Hailstone, a renowned expert in energy management and renewable energy, who brings a wealth of knowledge on electricity delivery and grid reliability. With his deep understanding of global energy markets and their intersection with geopolitics, Christopher offers unparalleled insights into the complex dynamics of Western sanctions on Russia’s energy sector. In this interview, we explore the effectiveness of these sanctions, the innovative ways Russia has adapted, the role of other global players, and the broader implications for energy security and international relations.

How would you describe the concept of ‘peak sanctions’ in the context of Western efforts to target Russia’s energy sector?

When we talk about ‘peak sanctions,’ we’re referring to a point where the West has essentially exhausted its most impactful tools to pressure Russia through economic restrictions on its energy sector. Over the past decade, and especially since the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, the U.S. and Europe have dramatically ramped up sanctions, targeting everything from oil exports to specific entities and individuals. However, the sheer volume and prolonged use of these measures have started to diminish their effectiveness. Russia has adapted by finding workarounds, and the cost of enforcement for Western nations and companies has skyrocketed. It’s like hitting a wall—there’s only so much you can do before the impact starts to wane, and I think we’re seeing that now.

Can you walk us through the massive increase in sanctions on Russia since the 2022 invasion of Ukraine and what that escalation looks like?

Absolutely. The surge in sanctions post-2022 has been staggering. Before 2013, the European Union had virtually no sanctions on Russia, but by 2025, that number has climbed to over 2,500. The U.S. has been even more aggressive, adding more than 3,100 new entities and individuals to its lists just last year, with about 70% of those being Russian. This isn’t just about quantity—it’s about scope. We’ve seen both primary sanctions, which directly block dealings between Western countries and Russia, and secondary sanctions, which target third parties doing business with sanctioned entities. It’s created a sprawling web of restrictions aimed at choking Russia’s energy revenues, but it’s also made compliance incredibly complex and costly for global businesses.

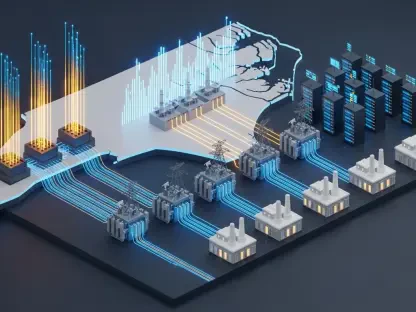

Russia has reportedly found ways to bypass these sanctions using what are called ‘dark fleets.’ Could you explain what those are and how they work?

Dark fleets are essentially a shadow network of tankers used to transport Russian oil and gas while evading Western oversight. These ships often operate without proper insurance or registration tied to Western systems, making it hard to track their movements or enforce sanctions like price caps. They’re a workaround that allows Russia to continue exporting to key markets like China and India, which account for about 80% of its crude sales. This isn’t unique to Russia—Iran and Venezuela have used similar tactics for years under heavy sanctions. The dark fleets undermine the West’s ability to control the flow of Russian energy, showing just how adaptive the industry can be when faced with restrictions.

Speaking of markets like China and India, how are these countries playing a role in helping Russia navigate around Western sanctions?

China and India have become critical lifelines for Russia’s energy exports since the sanctions intensified. They’ve stepped in as major buyers of Russian crude and gas, often at discounted rates, which helps Moscow maintain revenue streams despite Western efforts to cut them off. Beyond just purchasing, there’s evidence of deeper involvement—China, for instance, imported liquefied natural gas from a heavily sanctioned Russian plant in August, a move that signals a willingness to prioritize economic ties with Russia over Western pressure. Both countries have also been implicated in facilitating alternative trading and financing networks, which further dilute the impact of sanctions. It’s a pragmatic approach for them, driven by energy needs and geopolitical alignments.

Let’s talk about the G7’s price cap on Russian crude oil, initially set at $60 per barrel. How effective has this measure been in curbing Russia’s energy profits?

The price cap was a creative idea—to keep Russian oil flowing to avoid global price shocks while limiting Moscow’s revenue by capping what buyers could pay using Western services like insurance. However, it’s largely fallen short. Russian Urals crude has traded above the $60 cap for about 75% of the time since it was introduced in December 2022. The dark fleets I mentioned earlier play a big role here, as they enable sales outside Western oversight. Even with recent adjustments by the EU and some G7 members to lower the cap to $46.50, the effectiveness remains questionable. Russia’s ability to find alternative buyers and logistics solutions means the financial hit hasn’t been as severe as hoped.

Despite some revenue losses for Russia due to these sanctions, the impact hasn’t shifted their stance in the ongoing conflict. Why do you think that is?

That’s a critical point. Estimates suggest Russia has lost around $154 billion in direct tax revenue from crude sales over the past few years due to sanctions, which is significant since oil and gas make up a quarter of their federal budget. But this hasn’t been enough to force a policy change regarding the war in Ukraine. Part of the reason is that Russia has diversified its markets—China and India have filled much of the gap left by Western buyers. Additionally, the Kremlin has shown a remarkable tolerance for economic pain, prioritizing geopolitical goals over short-term financial losses. Sanctions were meant to pressure a swift end to the conflict, but three and a half years in, it’s clear they haven’t achieved that strategic objective.

What does China’s recent import of LNG from a sanctioned Russian plant tell us about the broader challenges of enforcing these Western sanctions?

China’s import of LNG from Russia’s Arctic LNG 2 plant in August is a glaring example of the cracks in the Western sanctions regime. It shows that some major powers are willing to openly defy or at least sidestep these restrictions when it suits their interests. This wasn’t just a quiet transaction—it happened right before a high-profile visit by the Russian president to China, almost as a statement of economic solidarity. It highlights a fundamental challenge: sanctions rely on global cooperation to work, but when key players like China prioritize their energy needs or strategic partnerships with Russia, the West’s leverage diminishes. It also complicates U.S.-China relations, adding another layer of tension to an already strained dynamic.

Looking ahead, what is your forecast for the effectiveness of Western sanctions on Russia’s energy sector in the coming years?

I think we’re likely to see a continued decline in the effectiveness of these sanctions unless there’s a major shift in global cooperation or enforcement mechanisms. Russia has already proven adept at finding workarounds, and as long as countries like China and India remain willing buyers, Moscow will have breathing room. The West might keep tightening the screws—adding more entities to sanction lists or lowering price caps—but history shows that prolonged sanctions often lead to adaptation rather than capitulation. Without a broader coalition or innovative approaches to enforcement, I suspect we’ll see diminishing returns. The bigger question is whether the West can balance its own economic stability with the desire to maintain pressure on Russia, especially as energy markets remain volatile.