With extensive experience in energy management and a deep understanding of grid reliability, Christopher Hailstone joins us to unpack the complexities of Venezuela’s struggling yet resilient oil refining sector. We will explore the recent surge in processing capacity, the persistent operational challenges that threaten this progress, and the dual strategies PDVSA is employing—from reconfiguring domestic assets to importing U.S. products—in a desperate bid to meet the nation’s fuel demands.

Venezuelan refineries recently boosted processing to about 35% of capacity, up from last year’s 25%. What specific operational changes contributed to this increase, and what are the primary challenges to sustaining this higher level of output?

The increase to 450,000 barrels per day is a significant achievement, but it’s built on a very fragile foundation. The primary driver has been a concerted effort by PDVSA to simply keep the essential fuel-making units online, which is a constant battle. They’re also cleverly reconfiguring some of the crude upgraders in the Orinoco Belt to produce more suitable feedstock for the refineries. However, the biggest challenge is the grid. These facilities are constantly hammered by power outages and malfunctions. You can make progress for weeks, and then a single blackout, like the one that recently hit the Amuay refinery, can wipe it all out and force you to start over. Sustaining this output isn’t about innovation; it’s about sheer resilience against a failing infrastructure.

When a major facility like the Paraguana Refining Center recovers from a blackout to process 287,000 bpd, what is the step-by-step process for restarting operations? Could you elaborate on the key technical vulnerabilities that make these facilities so susceptible to frequent malfunctions?

Restarting a massive complex like Paraguana after a sudden shutdown is an incredibly delicate and dangerous process. First, you have to ensure the external power supply is stable, which is never a guarantee. Then, you begin the slow, methodical process of bringing the distillation units back online one by one, carefully managing temperatures and pressures. Imagine trying to reignite a colossal, intricate furnace without causing an explosion. The key vulnerability is age and a lack of investment. Decades of neglect mean that every component, from pumps to control systems, is brittle. The sudden stress of a shutdown and restart is often what causes the next malfunction, creating a vicious cycle of breakdown and repair.

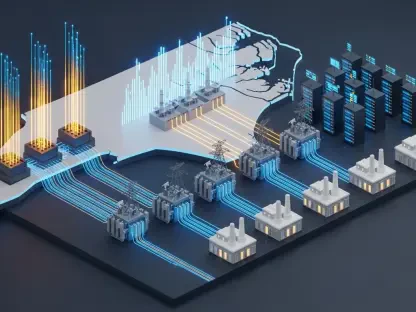

PDVSA is reportedly reconfiguring crude upgraders in the Orinoco Belt while also importing U.S. naphtha. Can you explain the practical difference between these two strategies and how each one helps address the country’s domestic fuel shortages?

These are two very different solutions to the same problem: getting the right kind of raw material. Reconfiguring the Orinoco upgraders is an internal, self-sufficient strategy. They are modifying these plants, which normally turn extra-heavy crude into a lighter synthetic crude for export, to instead produce feedstock tailored for their own domestic refineries. On the other hand, importing U.S. naphtha is an external fix. It serves a dual purpose: it can be used directly as a diluent to make the Orinoco’s tar-like crude flow through pipelines, and it’s a critical component for blending into high-octane gasoline. The first approach leverages domestic assets, while the second relies on foreign supply to bridge immediate gaps.

With the refining network now processing around 450,000 bpd, this output is still considered low for meeting domestic needs. How large is the gap between current fuel production and estimated national demand, and which specific products face the most critical shortfalls?

Even at 35% capacity, there’s a significant shortfall. While it’s an improvement, you have to remember the system was designed to run at 1.29 million barrels per day. The current output is barely enough to keep the lights on and some cars moving. The most critical shortages are in transportation fuels—gasoline and diesel. You see this reflected in the constant rationing and long lines at service stations across the country. They are forced to prioritize, but there simply isn’t enough finished fuel to power a nation, even one with a depressed economy. This forces them to rely on imports like naphtha just to produce enough gasoline to prevent a total standstill.

What is your forecast for Venezuela’s refining sector?

My forecast is one of cautious, and perhaps fragile, stability. I don’t see a dramatic return to full capacity anytime soon, as that would require massive capital investment that simply isn’t available. Instead, we’ll likely see this pattern continue: periods of increased output, reaching maybe 40-45% capacity, followed by inevitable setbacks from equipment failures and power outages. The reliance on U.S. naphtha imports will be a crucial variable, heavily dependent on the geopolitical climate and sanctions. The sector will likely limp along, doing just enough to stave off a complete collapse, but remaining a shadow of its former self for the foreseeable future.