Wyoming, long celebrated as the nation’s undisputed king of coal, is now confronting a sobering reality as its most vital industry enters a seemingly irreversible decline, threatening the very economic foundation upon which the state has been built for more than half a century. Production has plummeted from its 2008 peak of over 466 million short tons to a projected 200 million tons, making 2025 the second-worst year in the industry’s modern history. This catastrophic drop is not merely a cyclical downturn but a powerful signal of a structural shift in the American energy landscape, forcing a state that has prided itself on fiscal independence to stare into a future of profound uncertainty and politically challenging decisions. The crisis raises a critical question about whether any amount of political will or state-level intervention can hold back the overwhelming tide of market forces that are fundamentally reshaping how America generates its power.

The Economic Bedrock Crumbles

A State Built on Coal

For generations, the economic identity of Wyoming has been inextricably linked to the rich coal seams of the Powder River Basin, a resource that has done far more than simply power the nation. The revenues generated from taxes, royalties, and fees on coal production have served as the financial backbone of the state, allowing it to fund essential public services like schools, infrastructure, and parks without the need for a state income tax. This unique fiscal structure, which in 2022 alone saw the industry contribute over $563 million to state coffers and support around 12,000 jobs, has fostered an environment of low taxation and economic stability. The reliable stream of income from coal enabled the creation of a substantial sovereign wealth fund, providing a financial cushion that has long been the envy of other states. This prosperity was not just a line item in a budget; it defined the quality of life and the social contract for Wyoming’s residents, creating a deeply ingrained reliance on a single, dominant industry.

The deep-seated dependence on coal revenue cultivated a unique political and economic ecosystem in Wyoming, where the health of the industry was synonymous with the health of the state itself. This symbiotic relationship fostered a stable, business-friendly climate that insulated it from the economic volatility experienced elsewhere. Over the last fifty years, this model allowed the state to maintain competitive sales taxes and even reduce property taxes, making it an attractive place for both individuals and businesses. The wealth extracted from the ground was reinvested directly into communities, building a legacy of public infrastructure and shared prosperity. However, this long period of stability also engendered a vulnerability. By building its entire fiscal house on a foundation of coal, Wyoming left itself exposed to the very market shifts that now threaten to dismantle the prosperity it so carefully constructed, revealing the inherent risks of an economy that bets its future on a single, finite resource.

Facing a Fiscal Cliff

The precipitous decline in coal production and revenue has pushed Wyoming’s economic future onto what Robert Godby, a University of Wyoming economist, describes as profoundly “shaky ground.” The gradual erosion of the state’s primary income source is no longer a distant threat but an immediate crisis that is forcing a difficult reckoning within the state legislature. The looming budget shortfalls are compelling lawmakers to confront a series of “really difficult political decisions” that were once considered unthinkable in this traditionally conservative, low-tax state. The most significant of these is the potential creation of a state income tax, a measure that would fundamentally alter the fiscal compact with its citizens. Alternatively, the state may need to consider substantial increases in sales or property taxes, moves that would be deeply unpopular and could stifle economic growth. These are not just administrative adjustments; they represent a potential unraveling of the economic model that has defined Wyoming for decades.

This fiscal crisis extends far beyond budget spreadsheets and political debates, threatening to impact the daily lives of every resident. A significant reduction in state revenue could lead to austerity measures affecting public education, healthcare services, and the maintenance of critical infrastructure like roads and bridges. Public sector employment, a significant source of stable jobs in many communities, could face cuts, creating a ripple effect throughout the local economy. Furthermore, a diminished quality of public services combined with a higher tax burden could make it harder to retain and attract a skilled workforce, potentially leading to a “brain drain” as younger generations seek better opportunities elsewhere. The challenge for Wyoming is not merely to balance a budget but to reimagine its entire economic identity in a world that is rapidly moving away from the very commodity that once guaranteed its prosperity and stability.

The Unstoppable Force of the Market

Why Coal is Losing the Race

At the heart of coal’s decline is a simple and unforgiving economic reality: it has become more expensive to generate electricity from coal than from its competitors. The majority of the nation’s coal-fired power plants are aging, many having been in operation for several decades. Much like an old car, these plants are becoming less efficient and more costly to maintain. Economist Robert Godby’s analogy is particularly apt; investing in major repairs for an old vehicle eventually ceases to make financial sense when a new, more reliable and efficient option is available. For utility companies, the “new car” is increasingly a natural gas facility or a renewable energy project. While Wyoming’s Dry Fork Station, built in 2011 and located less than a mile from its fuel source, remains competitive, it stands as a stark exception that proves the overarching rule. The industry has not seen widespread investment in new coal plants for over a decade because the economic calculus no longer supports it, a clear signal that the market has moved on.

The economic headwinds facing coal are compounded by a confluence of technological, regulatory, and logistical factors. As coal plants age, their thermal efficiency decreases, meaning they burn more fuel to produce the same amount of electricity, driving up operational costs. Simultaneously, evolving environmental regulations often require the installation of expensive pollution control technologies, or retrofits, to mitigate emissions of substances like sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and mercury. These capital-intensive upgrades can be difficult to justify for a plant nearing the end of its operational life. Furthermore, the logistical chain for coal, which involves extensive mining operations and long-distance rail transport, adds another layer of expense that natural gas pipelines and localized renewable projects do not share. This combination of rising internal costs and the falling price of alternatives has created a powerful market current that is pulling the energy sector away from coal, a trend driven not by ideology but by fundamental business economics.

The Market’s Final Verdict

The pro-coal agenda of the Trump administration, which included rolling back environmental regulations and opening federal lands to new leasing, served as a crucial test of whether political intervention could revive the industry. Despite these significant supportive measures, the administration’s efforts could only marginally slow the industry’s decline, not reverse it. The most definitive and undeniable evidence of the market’s verdict came from the failure of federal coal lease sales in the Powder River Basin, the nation’s premier coal-producing region. After years of industry disinterest, new sales were scheduled, yet a sale in Montana was canceled because bids from coal companies were too low for the government to legally accept. A subsequent sale in Wyoming was indefinitely postponed. This public failure was irrefutable proof, as Robert Godby noted, that “even the White House can’t offset markets.” When companies refuse to invest in new reserves even under the most favorable political conditions, it sends an unambiguous signal that they see no profitable long-term future for the commodity.

The reluctance of coal companies to bid on new leases revealed a strategic shift occurring within the industry itself. This was not merely an external market force acting upon the industry, but an internal consensus that future capital investment in thermal coal was no longer a sound financial strategy. Faced with declining demand from domestic utilities, increasing competition from natural gas and renewables, and growing pressure from investors over environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria, these companies began to prioritize managing their existing assets for cash flow rather than expanding their operations. Their actions demonstrated a clear-eyed assessment of coal’s diminishing role in the future energy mix. The empty auction blocks in the Powder River Basin were not just a sign of temporary weakness; they represented a calculated retreat from what was once the most profitable and promising region for American coal production, effectively closing a chapter on the industry’s era of growth.

A Glimpse into the New Energy Landscape

The Inevitable Transition

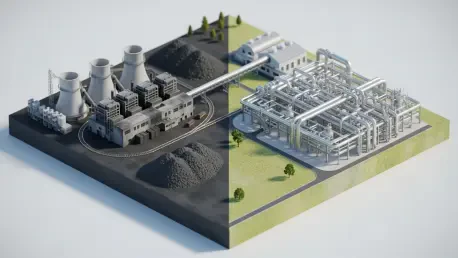

The movement away from coal is not a phenomenon unique to Wyoming but is part of a sweeping, global energy transition. Across the United States, utility companies are methodically executing long-term plans to retire their aging coal fleets, driven by the superior economics and operational flexibility of other energy sources. This shift is tangible within Wyoming itself, as exemplified by the Naughton power plant, which is in the process of a full conversion from coal to natural gas. This local example mirrors a much broader international trend. In recent years, renewable energy sources like wind and solar have officially surpassed coal as the leading source of electricity generation worldwide. This milestone marks a fundamental and likely permanent evolution in the global energy system. The world is not just supplementing its energy mix with new technologies; it is actively reordering it, with coal being systematically displaced from its long-held position of dominance.

This ongoing transformation is establishing a new energy paradigm based on a more diversified and decentralized system. In this emerging model, renewable sources are increasingly forming the foundation of the grid, providing clean, low-cost power when conditions are favorable. Natural gas, with its ability to be dispatched quickly, is carving out a crucial role as a flexible fossil fuel backup, ensuring grid stability when solar and wind generation wanes. In this reconfigured system, the traditional role of coal as a baseload power source is becoming obsolete. It is being outcompeted on cost by renewables and on flexibility by natural gas. The result is a structural shift where coal is no longer an essential component of the grid but rather an aging, economically challenged technology being squeezed out by a more dynamic and cost-effective combination of modern energy solutions. This is the new reality that states like Wyoming must navigate.

The Challenge of Reinvention

In a determined effort to protect its foundational industry, Wyoming’s leadership pursued a multi-pronged defensive strategy. The state implemented tax cuts aimed at providing financial relief to struggling coal companies, initiated a series of legal challenges against federal regulations perceived as harmful to the industry, and invested public funds into research on alternative uses for coal. A significant focus of this research was on carbon capture, utilization, and sequestration (CCUS) technologies, which held the promise of allowing coal to be burned with a greatly reduced carbon footprint. However, these measures were largely seen as a rearguard action against an overwhelming economic tide. Despite years of research and investment, CCUS technology has remained prohibitively expensive and has not yet been proven to be commercially viable on the scale needed to salvage the industry. These efforts, while born of a desire to preserve jobs and revenue, ultimately could not overcome the fundamental market forces driving the energy transition. The state’s last stand highlighted the immense difficulty of saving an industry when its core product was no longer economically competitive.